This article was written by Karl Siegling, Managing Director & Portfolio Manager, Cadence Capital Limited (ASX: CDM)

Following on from our first two articles on investor behaviour and emotion, we will briefly outline an oversimplified way of dealing with market and human behaviour.

We will then dedicate a number of articles to how different investors actually arrive at “fundamental value,” “fair value,” “intrinsic value” and all the other methods or tools used that attempt to categorically arrive at a value for shares in any particular company.

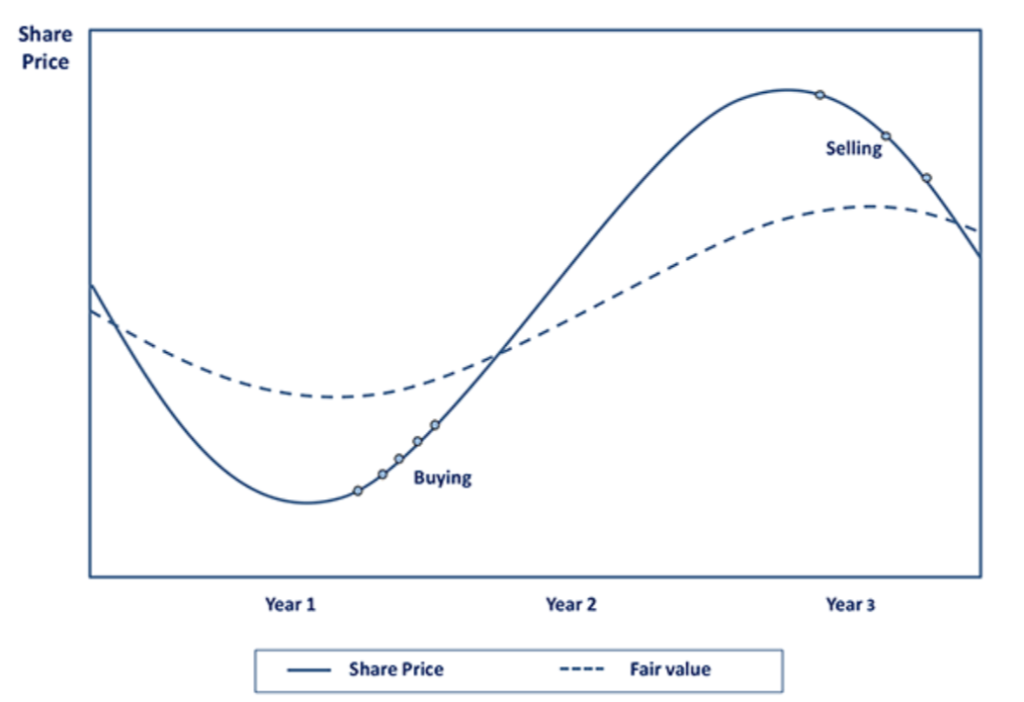

For the purposes of this illustration, we are once again going to make the fictitious assumption that we know ahead of time, or well into the future, what any particular stock is worth. I am going to call this assumption “fair value”.

As can be seen from the diagram below, “fair value” is illustrated as a dotted line and the actual share price for a stock is the solid line. For reasons outlined in our first two articles, stock prices should actually mimic the underlying fair value for stock earnings.

However, due to the emotions of hope, fear and greed, share price movement actually travels a more exaggerated path than underlying earnings and, as many investors will tell you, the share price movement for a stock actually moves ahead of new fundamental information.

Due to the emotions of hope, fear and greed, share price movement actually travels a more exaggerated path than underlying earnings

We will come back to the concept of stock prices actually being a good predictor of future earnings and the concept “that the market is always right”.

SHARE PRICE v FAIR VALUE

Source: Cadence Capital Limited

If we can accept that share prices “overshoot” on the way up and on the way down then we cannot simply buy shares when they are below “fair value” and sell them when they are above “fair value”.

This logic could lead to the very dangerous mistake of buying stocks when they are falling (while they overshoot on the downside) and selling stocks when they are going up (while they overshoot on the upside).

A basic rule of investment is to buy assets that are going up and sell assets that are going down – not buy assets on the way down and sell them on the way up. Hopefully, most investors have different methods for complying with this basic rule.

The way we buy and sell stocks is what we call “scaling into” and “scaling out of” positions. Each incremental buy adds to our overall position in a single stock, and each incremental sale reduces our position in a particular stock.

We believe this has the added benefit of not having to make drastic decisions on an entire position and drastically reduces unnecessary worry over any one particular buy or sell decision.

This method, properly implemented, allows us to make greater returns by letting profits run longer and cutting losses earlier, as well as avoiding additions to losing positions.

We feel so strongly about not adding to losing positions that I would argue the single biggest mistake that most investors make is actually adding to losing positions – followed closely by not letting winning positions run.

The temptation to hang onto losing positions and sell winning positions is the very emotional hurdle that stops many investors from producing better returns. We have hopefully implemented a more evolved version of the diagram outlined above to prevent the roller-coaster ride of emotion from entering into our investment decisions.

The first three articles on investor behaviour give a simplified version of some of the behavioural issues to be considered independently of any fundamental analysis.

A short illustration of these concepts hopefully goes some way in getting us to consider these issues but cannot do the areas of behavioural sciences the necessary time or credit that they deserve in the investment arena.

We strongly encourage all investors, including our portfolio managers, to remind themselves from time to time about the behaviour of the market and to read the many investment books and interviews on the topic.

Having positioned the investment process within a behavioural framework, we will move onto outlining fundamental analysis over the coming weeks.

Written by Karl Siegling, Cadence Capital Limited